The last 100 years of transit and transportation planning in Los Angeles hold stories full of challenges and opportunities, successes and failures, and some surprises, little known “firsts,” and enduring urban legends.

We are taking a look back — decade by decade — at key resources from our collection to contextualize the seminal traffic, transit, and transportation plans for the region in order to provide greater understanding of how we arrived where we are today.

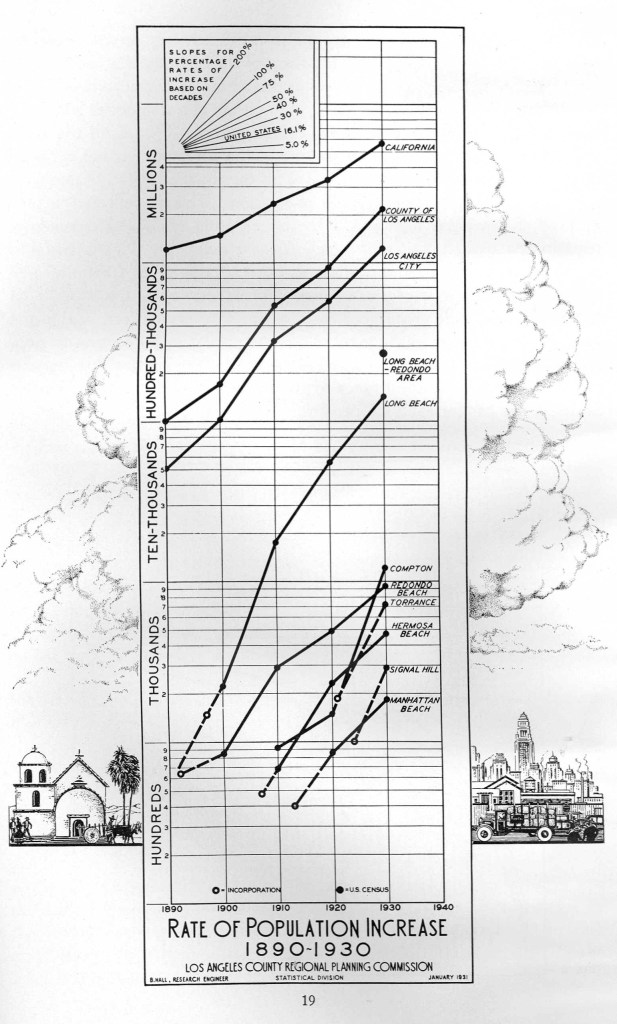

The rapid growth of Los Angeles in the 1920s was met with the economic uncertainty of the 1930s.

As the new decade dawned, the Board of City Planning Commissioners held a Conference on the Rapid Transit Question on January 21, 1930.

The program included addresses given by local political and business figures as well as Los Angeles Railway and Pacific Electric Railway executives, along with perspectives from other cities, including Long Beach, Santa Monica and Whittier.

Donald M. Baker, President of the Board of City Planning Commissioners argued that “we are here more to define than to solve the problem…that is what our engineering President Herbert Hoover terms a quantitative or engineering method of attack.”

He goes on to frame the problem in terms that remain familiar today: Los Angeles’ rapid growth, decentralization, atypical urban development, complex city boundaries, need for highway planning, the relationship between transit and the rest of the built environment, and financing during a national economic collapse.

Los Angeles Mayor John C. Porter proposed that the question of rapid transit “should be considered from a County-wide viewpoint…maybe go further than that,” perhaps one of the first critical nods to a regional approach to transit planning.

In the report, D.W. Pontius, President of Pacific Electric Railway, noted an overarching concern that would haunt transportation planners for many decades to come: “Our problem then is to prevent the present increasing traffic congestion conditions from becoming intolerable, which would result in Southern California being pointed to as an undesirable place to live, which would be exactly the opposite to our national and international reputation at this time.”

Another landmark report was issued in 1930. Parks, Playgrounds and Beaches for the Los Angeles Region was submitted to the Citizens’ Committee on Parks, Playgrounds, and Beaches by Olmsted Brothers and Bartholomew and Associates.

This report is an exhaustive survey of recreational opportunities in Los Angeles, along with extensive recommendations for the rapidly growing city. It is one of the region’s earliest urban planning documents concerned with quality of life as it relates to transportation, recreation, and access to both.

In order to stave off the “undesirable” moniker, the report recommends addressing the “urgent need for a system of interconnected pleasureway parks, regional in scope.”

1930: Green = existing, Red = proposed

1930: Green = existing, Red = proposed

It explains that recreational areas could be brought into the expansive neighborhoods by creation of “elongated real parks” with roadways through them to expedite traffic. The intent was to limit unnecessary automobile use in driving from “uninteresting streets” as opposed to proposed routes spacious enough for trees and screened from urban surroundings.

Some of the other proposals were practical and carried out, while others were extremely ambitious. The “East Side Highway Study Plan” for areas of Monterey Park, Montebello, Whittier, Huntington Park, South Gate and Downey is a good example of capacity planning well into the future.

Still others were wildly fanciful and unrealistic, such as construction of a “pleasure harbor and oceanside park” stretching from Pacific Palisades to Marina del Rey.

As if parkways crisscrossing Los Angeles were not enough, this proposal suggested they also be built on a chain of islands in the ocean at the outside of the harbor.

The Executive Committee featured notable local luminaries like prolific real estate developer Walter H. Leimert, prominent attorney John O’Melveny, and iconic actress Mary Pickford. (O’Melveny later donated his former ranch in Granada Hills to the City of Los Angeles to create the city’s second largest park, O’Melveny Park)

The Great Depression halted progress on a comprehensive County of Los Angeles Regional Plan of Highways. The County Regional Planning Commission officially called for the project on May 21, 1923 but was only able to complete two sections before abandoning the project: San Gabriel Valley (1929) and Long Beach – Redondo (1931).

But the city continued to grow rapidly.

By 1931, Los Angeles County had nearly 50 named airports and landing fields…

…and plans for many more.

By 1932, the Great Depression was entering its third year. Los Angeles still welcomed the world to the Games of the X Olympiad, better known as the Summer Olympics.

They were the first Games of the Great Depression, and the city of 1.2 million residents managed to put on a spectacle that featured motor coaches transport athletes (one every minute!) and others a total of 83,360 miles without a single injury, delay, or failure of the system.”

Pacific Electric distributed a Program of Events instructing attendees on “how to reach all Olympic Events”…via The Big Red Cars and Motor Transit Stages. The city somehow managed to move athletes, equipment, workers, and attendees around the city without the benefit of subway rapid transit — an impressive feat that was replicated in 1984.

An extensive overview of transit and transportation during the 1932 Olympics can be found here.

In 1933, Donald M. Baker again proposed development of a rapid transit system, this time addressing the Central Business District Association “with the view of its being transmitted by your organization to the City of Los Angeles authorities.”

The report sought a loan of federal funds under the provisions of the National Industrial Recovery Act of 1933. It put into stark contrast the decline in rail and bus ridership compared to the rise in passenger car registration during the preceding dozen years.

traffic plans

traffic plans

Much of the proposed transit plans are predicated on completion of the approved Union Station for the city fronting Alameda Street at The Plaza.

It discusses possible future use of steam railroad rights-of-way, grade crossing elimination, and repurposing railroad facilites for rapid transit.

Perhaps most importantly, it puts forth the concept of four principle routes that are echoed in future transit plans: to Pasadena and the San Gabriel Valley; to Whittier and south to San Pedro; westward to the Santa Monica Bay region; and northward into the San Fernando Valley.

1937 stands out as a banner year for Los Angeles. The city celebrated Transportation Week with the launch of its new “modern streetcars” in a ceremony emceed by child actress Shirley Temple. This charming vignette itself has raised some questions about automobiles vs. public transit.

One key map explains the “normal driving time at five minute intervals from The Civic Center.”

One can see that the “normal” drive time from downtown to Santa Monica was 45 minutes. More than 90 years later, the wide range of freeway developments, street improvements, Metro Rail’s E (Expo) Line operations, bus rapid transit lines, micromobility options and bikeshare have hardly reduced the travel time and often it is even longer.

Despite the stagnant national economy, Los Angeles continued to prosper.

The 1937 Traffic Survey of the Los Angeles Metropolitan Area noted that

The destiny of the Los Angeles area has ceased to be a matter for speculation. It is now conceded by all who have watched its growth that it will become one of the largest population and commercial centers of the world. Future orderly growth is vitally dependent upon the establishment of a system of transportation lines serving all parts of the area.

Unfortunately, the plan also stated “We are not including a financing plan at this time.”

It did, however, put forth recommendations for “motorways,” land service streets and highways, motor vehicle parking and administration.

But public transit wasn’t being ignored. In a 1937 seminal Los Angeles Times feature article titled “Subway, Elevated — or What?,” the author describes the increasing congestion downtown, with streetcars clogging streets during a downpour that took motorists three hours to reach Beverly Hills.

The article takes an in-depth look at four different proposals dating back a dozen years:

| 1925 | Kelker DeLeuw proposal for a subway system, elevated railway tracks, and additional bus and streetcar suface facilities to serve as “feeders” |

| 1933 | Central Business District Association proposal which recommended a network of subways and elevated railways |

| 1935 | State Railroad Commission study and report on street railways suggesting closer cooperation between the two street railway companies, despite Pacific Electric’s “standard-gauge” tracks vs. Los Angeles Railway’s “narrow-guage tracks” |

| 1937? | Suggestions from Joseph B. Strauss (Golden Gate Bridge designer and builder) that Los Angeles should consider a suspended monorail like one in Germany, or a street-level and elevated bus system |

Further analysis of these and other proposals can be found in Evan W. Thomas’ 1939 UCLA Masters Thesis in Political Science titled An Analysis of Proposals to Provide Rapid and Adequate Mass Transportation for the Los Angeles Area.

The same year, the City of Los Angeles Transportation Engineering Board released their 1939 report following an 18-month study titled A Transit Program for the Los Angeles Metropolitan Area.

It finds that:

As far as mass transportation is concerned, the ultimate solution of the rapid transit problem in a large and densely populated area can be found only in rail rapid transit, and there is no doubt but that such a solution will eventually be necessary in portions of the Los Angeles Metropolitan Area.

The report puts forth a system of express highways and arterial parkways as the framework for a comprehensive transit and transportation system.

This landmark concept appears to have cemented the foundation for a rapid transit system predicated on highway planning — some of which was already under construction, such as the Arroyo Seco Parkway, America’s first freeway.

And while highway planning and viable public transit plans were being debated, Los Angeles’ decades-long battle over a Union Station ended with the opening of the Union Passenger Terminal on Alameda Street across from the ceremonial center of the city, the Plaza.

(Courtesy of USC Digital Library)

(Courtesy of USC Digital Library)

Three days of festivities prior to the May 7th opening attracted one-third of all Angelenos.

As the decade came to a close, a centralized station for heavy rail was settled, but firm decisions about highway planning and a mass transit proposal remained elusive.

While economic recovery was on the way, World War II was about to change daily life, leading to a manpower shortage and additional growing pains for the metropolitan area.

More Past Visions:

Past Visions of Los Angeles’ Transportation Future: 1920s

Past Visions of Los Angeles’ Transportation Future: 1940s

Past Visions of Los Angeles’ Transportation Future: 1950s

Past Visions of Los Angeles’ Transportation Future: 1960s

Past Visions of Los Angeles’ Transportation Future: 1970s

Past Visions of Los Angeles’ Transportation Future: 1980s

Past Visions of Los Angeles’ Transportation Future: 1990s

Past Visions of Los Angeles’ Transportation Future: 2000s

Past Visions of Los Angeles’ Transportation Future: 2010s